High-profile ransomware attacks against large businesses and governments have become increasingly popular. They typically occupy news headlines on a monthly basis. As of writing, the most recent, high-profile attack was launched against Porsche, South Africa, where IT systems and some backups were impacted by ransomware from an unknown attacker.

The gangs that perpetrate these attacks typically have carefully-crafted, large public personas and engage in significant posturing. These conscious PR efforts are an attempt to increase their popularity in order to attract affiliates to use their ransomware, but also to intimidate their victims.

The Lockbit ransomware gang

Not all groups fit this mould. One prolific operator has largely lurked in the shadows since its emergence onto the ransomware scene in late 2019. This group is known as Lockbit.

Despite Lockbit's shyness from the public spotlight, the group has been a relentlessly effective and professional ransomware actor. They have conducted a large volume of attacks against targets in the US, China, Ukraine, Indonesia and Western Europe. Their attacks feature triple extortion techniques that seek to disrupt business operations, blackmail victims into paying them large sums of money in exchange for the restoration of their data and systems, and confidential data exfiltration with the threat of publishing or selling victim data to the public. Most recently, Lockbit was responsible for an attack on Royal Mail that ground their international shipping operations to a halt, with the company asking customers not to ship items internationally for several weeks.

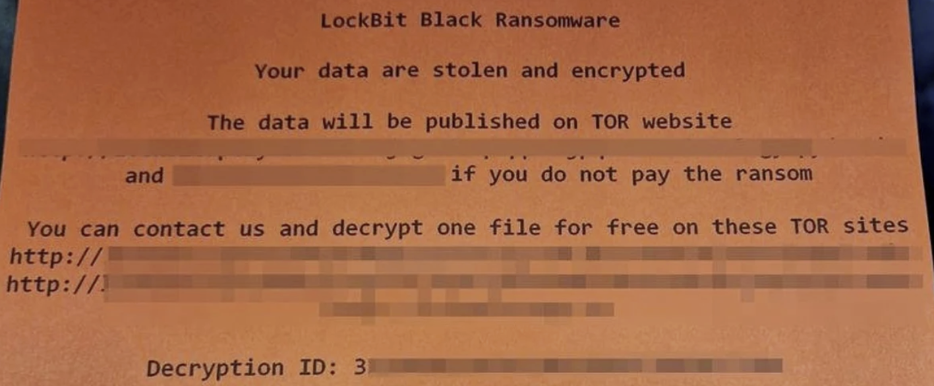

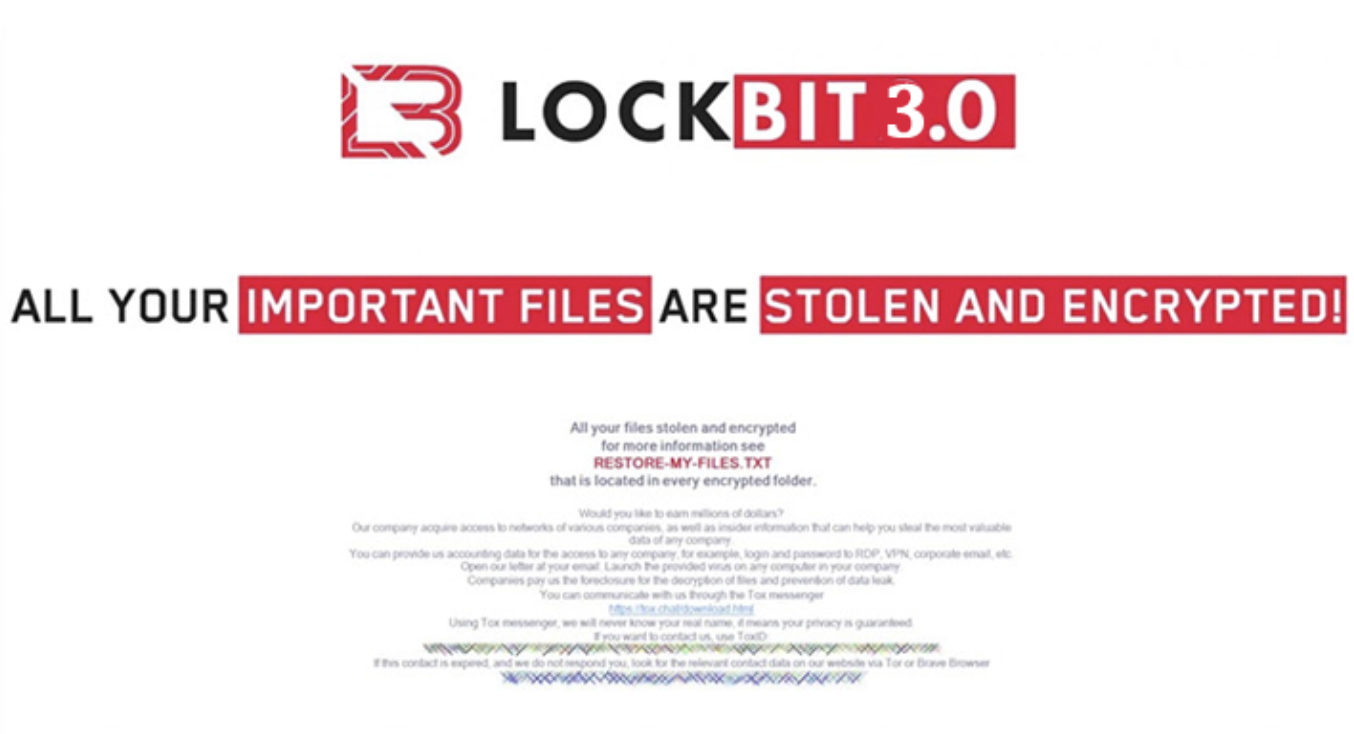

Figure 1: Lockbit ransom note during the Royal Mail attack (Source: Twitter @UK_Daniel_Card)

Figure 1: Lockbit ransom note during the Royal Mail attack (Source: Twitter @UK_Daniel_Card)

A prolonged negotiation over several weeks took place between the attackers and Royal Mail. Leaked screenshots have now surfaced from the conversation between Royal Mail and the Lockbit negotiator. The conversations suggest that Royal Mail never intended to pay the sizable $80 million ransom in exchange for their data, despite Lockbit's best attempts to intimidate and coerce the company into a timely payment. It is therefore no surprise that Royal Mail ultimately refused to pay the ransom and their stolen files were leaked online.

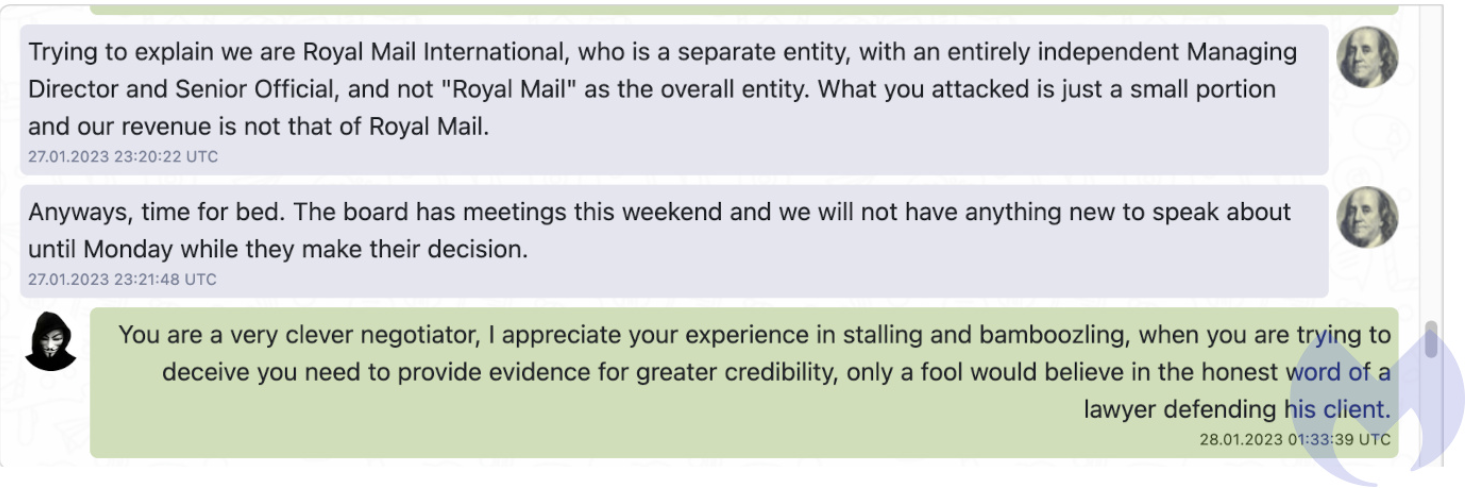

Figure 2: Lockbit and Royal Mail leaked negotiation (Source: Malwarebytes)

Figure 2: Lockbit and Royal Mail leaked negotiation (Source: Malwarebytes)

From the leaked messages, it is clear that the Royal Mail negotiator clearly set a timeline for the negotiations and was in no rush to concede to Lockbit, going as far as telling the Lockbit affiliate that it was "time for bed" and that he would "not have anything new to speak about until Monday". This clearly frustrated the Lockbit negotiator where he accused the Royal Mail representative of “stalling and bamboozling”.

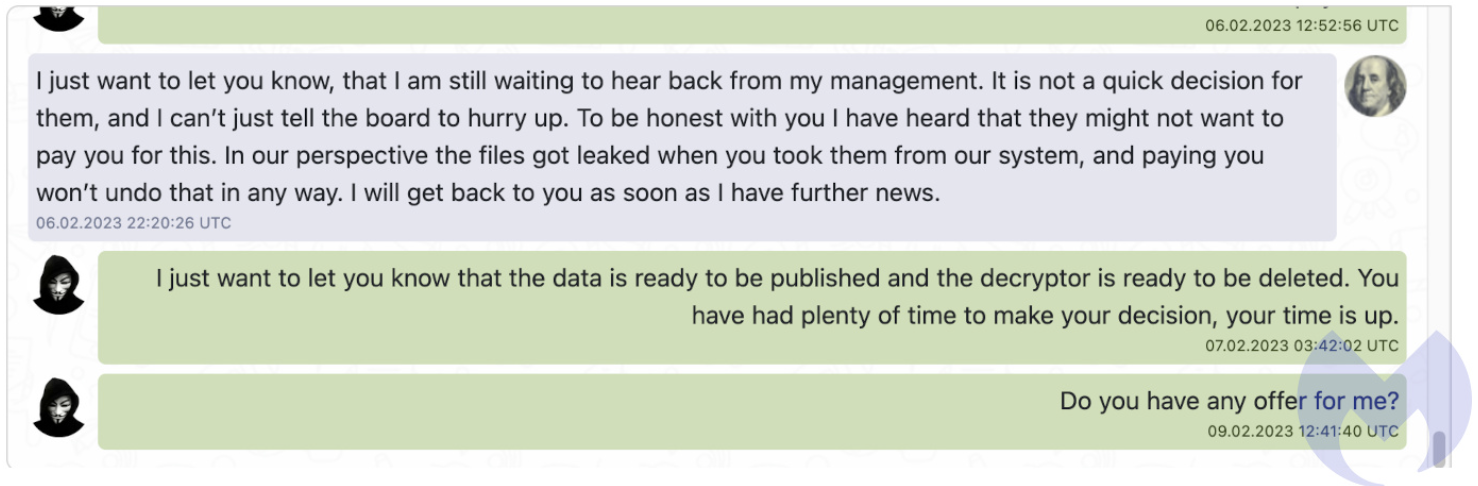

Figure 3: Lockbit and Royal Mail leaked negotiation (Source: Malwarebytes)

Figure 3: Lockbit and Royal Mail leaked negotiation (Source: Malwarebytes)

It is likely that the Lockbit affiliate realised that Royal Mail had no intention of paying the ransom and gave the company a final chance to make them a payment offer before the published the stolen data and deleted the decryptor.

This was an example of just one of many Lockbit attacks in recent months.

Lockbit is thought to be Russian in origin, with a significant portion of their operation being based in Russia. All members of the gang appear to be Russian-speaking and the group makes a conscious effort not to attack targets within Russia or the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). This is likely to avoid negative repercussions from Russian law enforcement.

Lockbit operates a Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) operation. Ransomware as a Service is a ransomware business model where the core group develops and maintains the ransomware software and licences it to third parties. The third parties will place a deposit for use of the software and launch attacks against victims. Profits from successful attacks are then split between the ransomware developer and the affiliated deployer. This model has allowed groups like Lockbit to profit from this lucrative malware, but also avoid many of the risks and complexities associated with conducting the attacks themselves.

This desire to stay lowkey has arguably led Lockbit to success and longevity within the space, something that many other groups have failed to achieve. This is particularly surprising as Lockbit is the most notorious ransomware gang in terms of attack volumes. The group was responsible for 51 separate ransomware attacks in January 2023 alone, 28 more attacks than the next most popular ransomware strain.

How does a Lockbit ransomware attack unfold?

A typical Lockbit attack will likely unfold via the following course of events.

Initial Access

In order for Lockbit to be executed and a ransomware attack initiated, initial access to the target network must be gained by the attacker. Initial access for Lockbit attacks is most commonly gained via phishing. These attacks exploit weaknesses in human behaviour and attempt to socially engineer users within the target company to click links within emails that contain payloads seeking to steal said user’s credentials. Phishing attempts may also seek to impersonate other employees within the organisation and attempt to convince a user to share their credentials. Alternatively, a Lockbit affiliate may gain initial access to a target network by the brute forcing of externally facing services like RDP accounts or VPN clients. These initial access vectors are not always found by the Lockbit affiliate, but can often be purchased from other criminal groups or dark web forums called Initial Access Brokers (IABs).

Execution

The exact method used will vary depending on the affiliate that launches the attack. However, Lockbit is typically executed via command line. The ransomware takes parameters including file and directory names if the attacker only wishes to encrypt certain files. It may also be executed via PowerShell using PowerShell Empire. PowerShell Empire is a post-exploitation hacking tool that creates stagers to an attacker’s C2 server. Windows PowerShell is a legitimate and powerful tool used by IT administrators, therefore PowerShell is typically whitelisted for use. This makes it a safe bet for attackers to utilise. Alternatively, Lockbit affiliates have also been observed using scheduled tasks via Group Policy Object to execute the ransomware and also evade detection. Scheduled tasks are widely used by legitimate software and operating system functions, and will likely appear benign without closer investigation. The attacker will search for a GPO that they can edit that has target devices within its scope. A scheduled task that executes the ransomware can be added to this GPO. Scheduled tasks can be utilised to execute binaries from user-writable directories like appdata/roaming. This allows the attacker to execute code across a network, regardless of privilege level.

Evasion

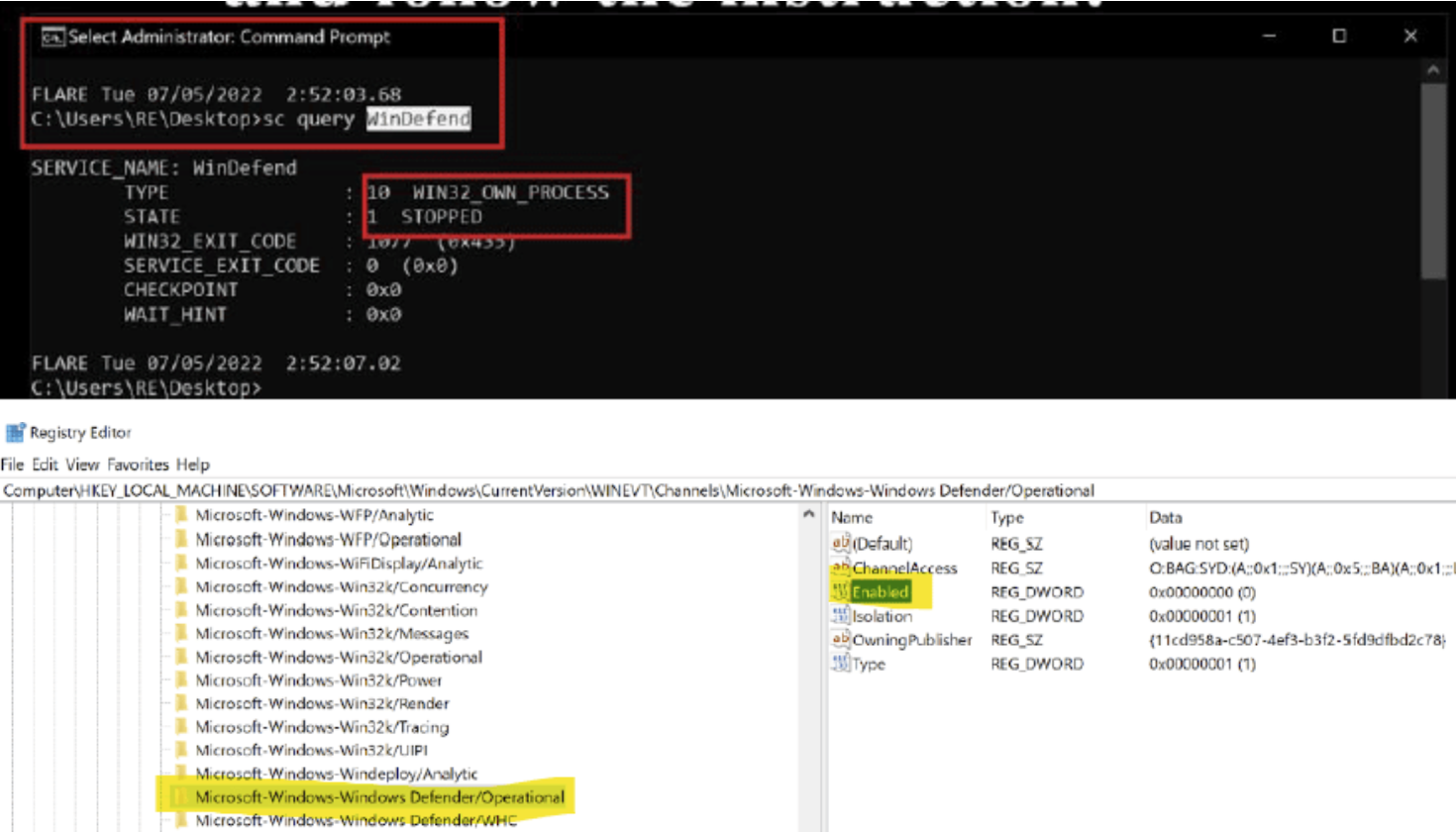

Lockbit will take steps to evade detection both during and after an attack. During an attack, Lockbit affiliates have been documented using Process Hacker and PC Hunter. Process Hacker is a legitimate tool used to find and stop running processes. Lockbit affiliates use this application to find and disable anti-malware associated processes and services. PC Hunter is another legitimate application that is used in a similar way by Lockbit affiliates as it gives access to system processes, kernel modes, and hooks. Additionally, Group Policy has been used during attacks to disable Windows Defender on a range of infected hosts, allowing the ransomware to slip by.

Figure 4: Lockbit disabling Windows Defender (Source: infosecinstitute.com)

Figure 4: Lockbit disabling Windows Defender (Source: infosecinstitute.com)

Lockbit developers have also taken significant steps to protect their intellectual property from being analysed after an attack. Lockbit 3.0 requires a passphrase to execute. This passphrase is only shared to affiliates that are launching attacks. This helps to prevent sandboxed analysis of the ransomware as the passphrase will need to be recovered with the sample of the malware. Furthermore, much of the Lockbit payload is only decrypted at runtime via XOR.

The ransomware stores in heap memory and utilises trampolines when functions are called. Function addresses called by the trampolines are obfuscated via XOR obfuscation techniques.

Lockbit developers have also built several mechanisms within the malware to detect whether it is being analysed by a debugger. Heap memory parameters are analysed such as the flags HEAP_TAIL_CHECKING_ENABLED and HEAP_VALIDATE_PARAMETERS_ENABLED. The presence of these flags typically suggests that a debugger is present. This makes dynamic analysis of the malware far more difficult.

Discovery

Lockbit targets with a network include Domain Controllers and Active Directory servers. These servers are typically targeted by ransomware as they hold large volumes of information about the network, can be used for privilege escalation, and can be used to spread the ransomware across the network at high speeds via GPOs. Lockbit attacks have been observed using Advanced Port Scanner and AdFind to enumerate connected machines in the network. AdFind is a legitimate command line tool used to query an Active Directory. It is used by IT administrators to find users, groups and subnet information about a domain. Unsurprisingly, ransomware operators use this tool to enumerate a network and establish paths for lateral movement.

Lateral Movement

Lockbit has been observed achieving lateral movement via SMB shares using stolen credentials. PSexec and Cobalt Strike have also been used by Lockbit to move laterally on a target network. Sysinternals PsExec is a tool used by IT administrators used to execute commands on a remote Windows machine. Similarly to other administrator tools that we have looked at, it can and has been used by ransomware operators, in conjunction with Local Administrator privileges on a compromised host, to execute code on another host. Cobalt Strike also enables an attacker to execute code on a remote host via WMI and PowerShell.

Data Exfiltration

Lockbit ransomware utilises StealBit to perform data exfiltration for double extortion before victim data is encrypted. StealBit is provided to affiliates by Lockbit along with the locker malware. After exfiltrating sensitive and confidential data from targeted, Lockbit will proceed with file encryption. The AES symmetric encryption algorithm is used to bulk-encrypt files. AES keys are then encrypted with a public RSA key and encrypted files are appended with the ".lockbit" extension. The ransomware then changes the inflected host's desktop background to a ransom note.

Figure 5: The desktop wallpaper displayed after a Lockbit 3.0 attack

Figure 5: The desktop wallpaper displayed after a Lockbit 3.0 attack

Lockbit 3.0

Lockbit 3.0, also known as Lockbit Black, is the most recent version of the group’s malware. It was released in mid-June 2022 after 2 months of beta testing and practice attacks. Changes to the encryptor are as of yet unknown, however the ransom note left on infected devices has changed from 'Restore-My-Files.txt' to a [id].README.txt naming format.

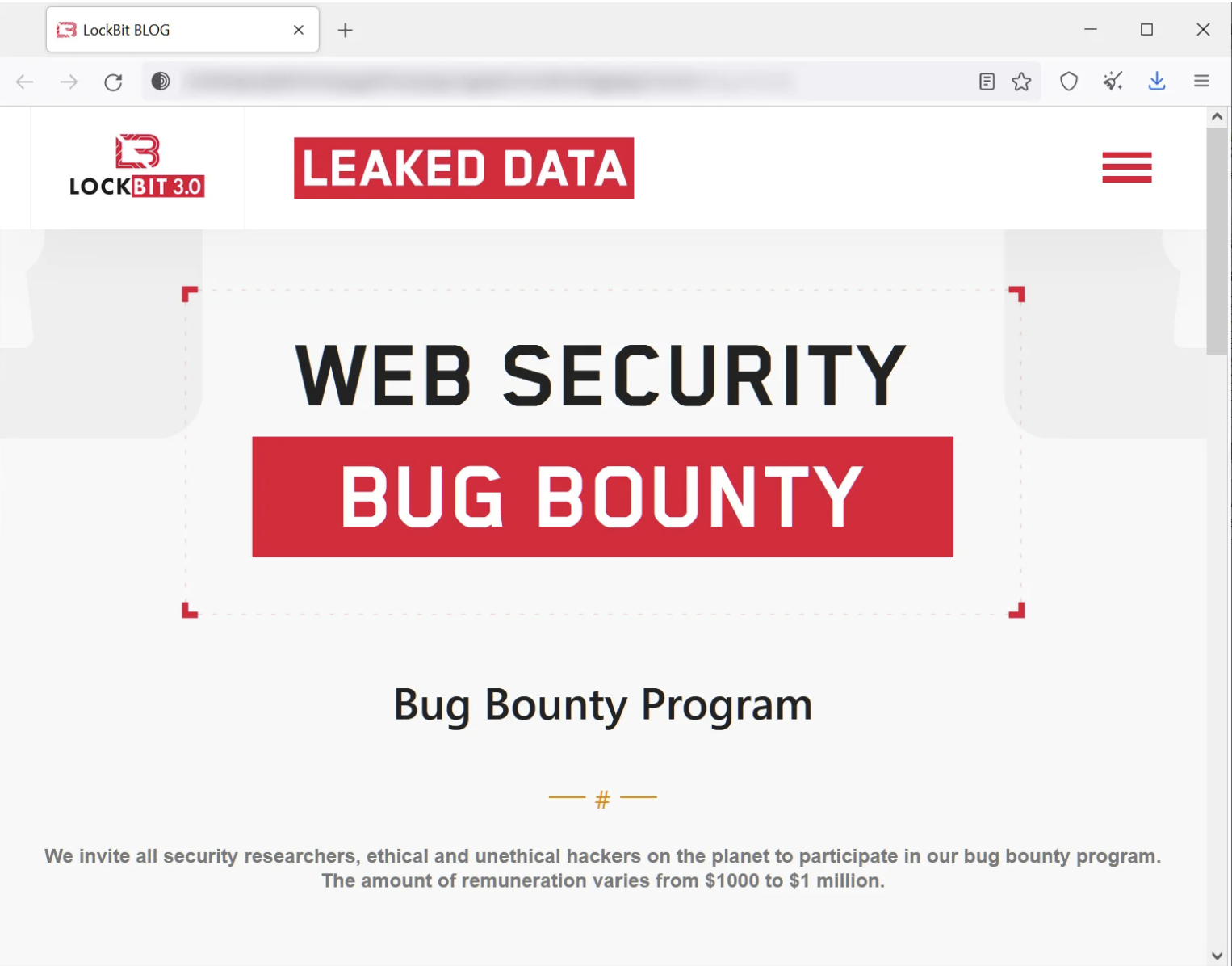

The Lockbit gang has proven to be a key innovator within the sphere of ransomware. Lockbit 3.0 features a first of its kind bug bounty program hosted by the gang. Legitimate security researchers and cyber criminals alike are encouraged to find and submit bugs in their website and locker software. They also offer a reward for the doxing of their affiliate program boss. Further compensation is said to be paid to those who submit "Brilliant Ideas" to the gang, including ideas for how to make their malware and services better. Lockbit has stated that they will pay anywhere between $1000 and $1 million for the above information.

Figure 6: Lockbit 3.0 bug bounty program

Figure 6: Lockbit 3.0 bug bounty program

How did a group that avoids attention become so successful?

Lockbit's ability to avoid attention is likely the source and not a hindrance to their success. Staging loud publicity stunts, as some ransomware gangs resort to, can be beneficial in the short term as it attracts new affiliates to conduct attacks. However, in the long term it appears to be a losing strategy. Excess attention will ultimately culminate in a target being placed upon a group’s back. Annoying a large state actor has historically never been a source of longevity for a criminal organisation.

Conversely, Lockbit's ability to conduct their business operations in a reliable and stable manner has built them a sound reputation within the cyber criminal underworld. Because of this, they are viewed as a reliable and professional partner to do business with and in return, the group attracts the best affiliates to deploy their ransomware.

What's changing?

Despite Lockbit's evident desire to remain inconspicuous and operate 'professionally', there have been several recent forays that have thrust the group into the public eye.

Just before Christmas 2022, Lockbit ransomware was used to attack SickKids, a Canadian children's hospital. This attack crippled internal IT systems and phone lines, resulting in disrupted medical treatments to the hospital's patients. Lockbit quickly walked back from the attack, offering the SickKids a free decryptor and publicly banning the affiliate who conducted the attack. Despite this, the attack drew wide scale public attention and scrutiny to the gang.

Additionally, evidence from the third quarter of 2022 has shown that Lockbit ransomware is being used to aggressively target industry and infrastructure. It is estimated that this malware was used in 1 in 3 ransomware attacks on industrial and organisations and national infrastructure. Attacks of this nature are often particularly damaging as they impact the availability and quality of public sector services and draw powerful state actors into the fray. Subsequently, these attacks can easily land a gang like Lockbit firmly within the crosshairs of powerful Western governments.

In fact, efforts to take down ransomware gangs like Lockbit have been in full swing. The FSB arrested key members of the REvil ransomware gang last year, Ukrainian intelligence infiltrated the Conti ransomware gang and leaked thousands of internal messages, greatly damaging the group’s image. Additionally, the US and UK governments recently named and sanctioned 7 members of the Conti and Trickbot ransomware gangs. Further pressure has come from the FBI and US Cyber Command who have admitted to actively targeting and attempting to disrupt the operations of these gangs.

Figure 7: Footage released by the Russian FSB after the arrest of REvil members in January 2022

Figure 7: Footage released by the Russian FSB after the arrest of REvil members in January 2022

It remains to be seen whether Lockbit will meet the same fate as these other notorious groups, however attracting excess attention by conducting increasingly distasteful attacks is a risky strategy for the group to employ.